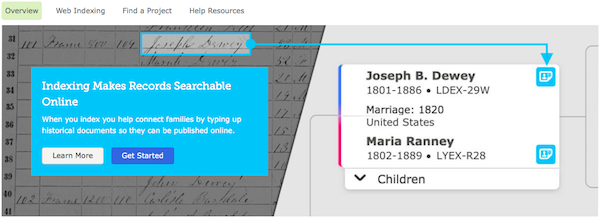

The major events in our ancestors lives have likely been recorded on paper. From birth and marriage certificates, to ship manifests and military records, there is a wealth of information out there. Thanks to technology, history is no longer just available on paper in isolated locations. FamilySearch has taken photographs of these priceless documents and volunteers throughout the world transcribe the information to make it searchable. This is called "indexing."

Over one billion records are now searchable since the volunteer effort began in 2006. I have benefited immensely from not only volunteering as an indexer, but from the records that others have transcribed. An example of this is with my ancestor, Robert Hutchinson.

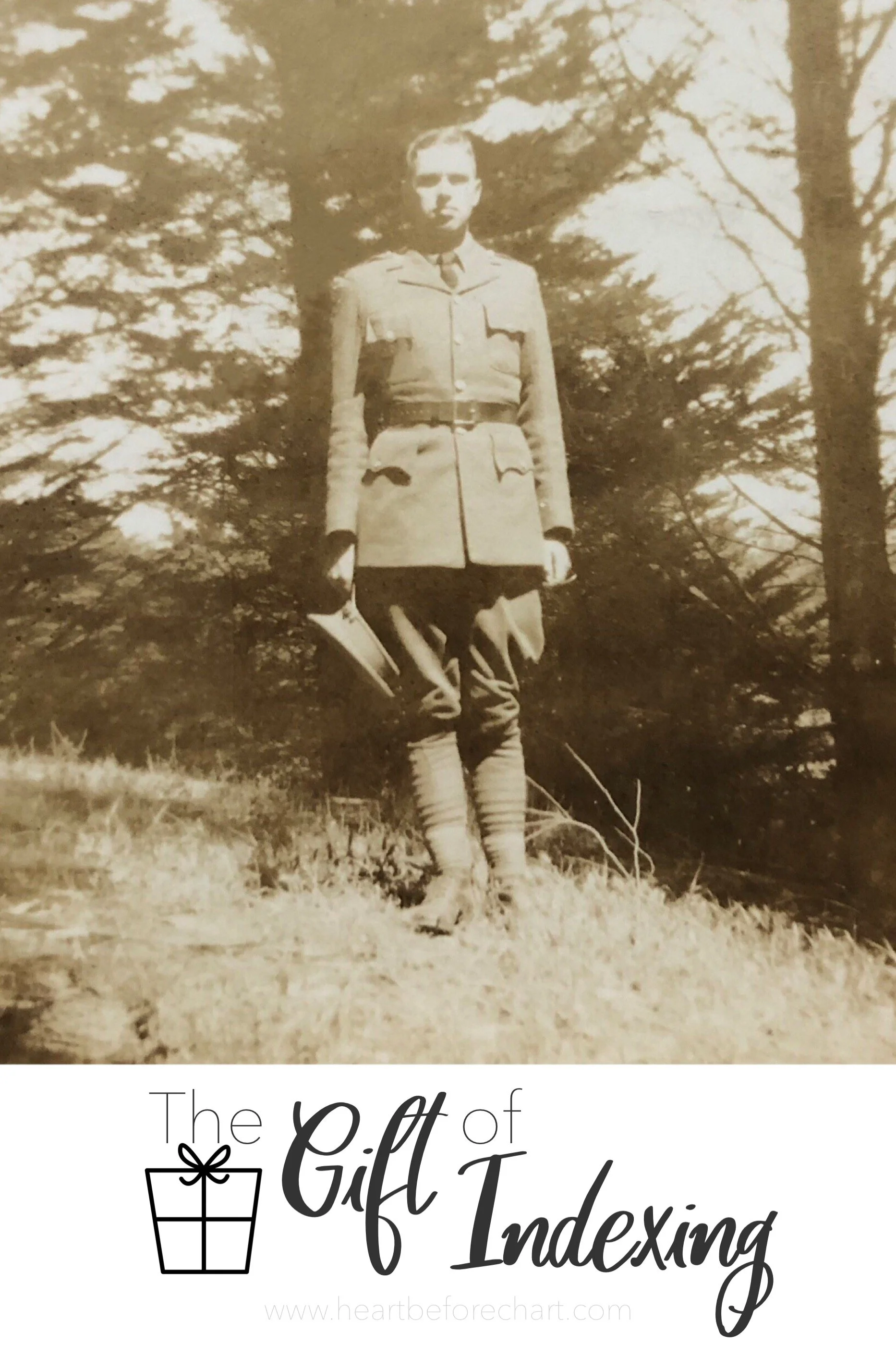

When visiting my parents last month, I was able to go through my grandmother's photo album and digitize the pictures. After I got home, I was trying to organize them in chronological order the best I could. When I got to one labeled "Robert Hutchinson," I had to refer to FamilySearch. I learned that he is my great-great-uncle and was just seven years older than my grandmother. He was born in 1901 and died in 1918. Since he was wearing what looked like a military uniform, I wondered if he had died in WWI.

The only sources available on FamilySearch were three images of his headstone and three mentions in family members' obituaries. I clicked on one of the headstone sources and saw that it was in Rockland, Idaho. Engraved were his birth and death dates, along with "BURIED AT SEA."

At this point, I was intrigued. He died October 13, 1918 and the war ended that November 11. How sad that he died one month before the conflict was over.

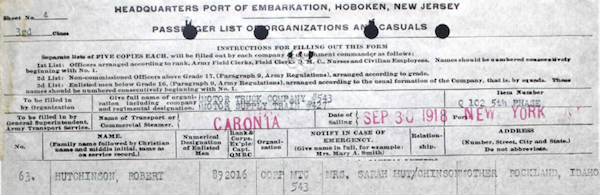

I wanted to know more details, so I searched Ancestry's website, but came up empty-handed. Ironically, when I used Google to search, two results came up on Ancestry. The first was a departure manifest for the ship "Caronia," leaving New York City, September 30, 1918.

From that manifest, I learned he was a Corporal in the in the Army Motor Transport Corps, trained to repair Army vehicles. I wish I knew how old he was when he enlisted since he shipped out at 17 and was already promoted beyond Private.

The other result was the return manifest for the ship arriving November 7, 1918. I was confused on why he would be on a return manifest when he was buried at sea when I scrolled to the top of the document. On it was stamped the word "DECEASED" in red ink. He, along with 73 other soldiers, died on that ship.

I still didn't know how they died, but I had the ship's name so I did a Google search for that and the year. One of the results was a book on Amazon that contained letters from a soldier that was also that ship. In the product description, it ended with, "Twelve days after the last letter [September 29, 1918], he dies of the Spanish flu aboard the HMT Caronia en route to England and is buried at sea."

The Spanish flu, an H1N1 virus, was the deadliest pandemic in history. It killed between 50-100 million people, one of whom was my great-great-uncle, Robert Hutchinson. It was insanely contagious and, once infected, the sick died quickly. It's no wonder the sailors were buried at sea and the ship returned so quickly.

I am able to share Robert's story with my family, and with you, all because the ship manifests were indexed and searchable.